Cultural Mapping in Practice - Cultural Mapping Examples

At Winyama, we know that mapping is more than just points on a page, it’s a way of story telling, honouring Country and protecting cultural knowledge for future generations. Unlike conventional mapping, cultural mapping centres Indigenous voices and culture. It’s not just about geography, it’s about memory, belonging and identity. Cultural mapping documents the places, stories, language and knowledge systems that hold significance to First Nations peoples. It’s a powerful tool for communities to reclaim, preserve and share our connection to Country on our own terms.

In this blog, we explore three case study examples that show cultural mapping in action. From collaborative work on Country to the use of emerging technologies, each story highlights a different approach to supporting self-determination and deepening our collective understanding of place.

Healing the Heart with Cultural Mapping

In June 2024, a powerful story of creativity, connection and community care travelled from Western Australia to a national stage. Community Arts Network (CAN) Executive Producer, Michelle White, and Aboriginal Advisory Group Chair, Geri Hayden, headed to Narrm (Melbourne) to present at the AIATSIS Summit.

Their session wasn’t just a presentation. It was an invitation into the heart of CAN’s long standing cultural mapping journey, grounded in deep collaboration with Noongar communities across Kinjarling (Albany), Katanning, Moora, Langford, Melville and Walyalup (Fremantle).

“Cultural mapping is really powerful, this could have finished a long time ago, and it’s still going 15 years on. The feedback from community members is, ‘We want that. We want to do that.’”

-Geri Hayden, Arts and Cultural Coordinator Aboriginal Programs

For many Elders, cultural mapping becomes a gentle yet powerful space to release emotions held tight for generations.

Elders and artists participating in cultural mapping workshop as part of Place Names Harvey

“Cultural mapping is like a healing for all our people, especially our Elders because for a lot of them, there’s things bottled up inside them that they can’t release. Being a part of the cultural mapping brings out the hurt and pain that people are suffering and it eases everything.”

-Geri Hayden, Arts and Cultural Coordinator Aboriginal Program

Workshops are welcoming and inclusive. Noongar people who may not be Traditional Owners are still invited to be part of the process, often finding belonging through their participation. The outcomes of this work are community-led, grounded in Country and centered on truth.. The cultural maps and artworks became not only expressions of truth and Country, they became living tools for education. Whether displayed in classrooms, libraries or cultural institutions, they invite Australians from all walks of life to engage with First Nations histories and knowledge systems.

Therefore, Cultural mapping continues to stand strong as an act of sovereignty.

Read the full article ‘Healing the heart with cultural mapping’

Mapping with Lifelines: Keystone Foundation’s Work to Protect Water in the Nilgiris

High in the Nilgiris mountains of southern India, water is more than a resource, it’s a lifeline. For generations, Indigenous communities there have relied on the springs and wetlands that flow through their landscape. But these waters are under strain, threatened by climate change, overuse and environmental degradation.

The Keystone Foundation, a not-for-profit grounded in both environmental stewardship and community wellbeing, has taken on the task of protecting these vital waters. Their work brings together technology, traditional knowledge and a collaborative spirit to keep water flowing, for the land, for the people and for the generations yet to come.

Keystone’s story began in 1994, when three friends set out on foot to survey honey gathering in Tamil Nadu. Carrying little more than backpacks and curiosity, they followed winding mountain tracks and backroads, meeting members of 11 Indigenous communities along the way. What they saw sparked a vision: to protect biodiversity and improve quality of life through eco-development, a model where caring for Country and caring for people go hand in hand.

Today, that vision runs through all of Keystone’s projects, but it’s their mapping work that has transformed how communities understand and safeguard their water sources. Using Google Earth Imagery, handheld GPS units, Android devices and even freehand maps drawn by locals, Keystone creates detailed GIS maps that chart springs, wetlands, land use, biodiversity and wildlife movement.

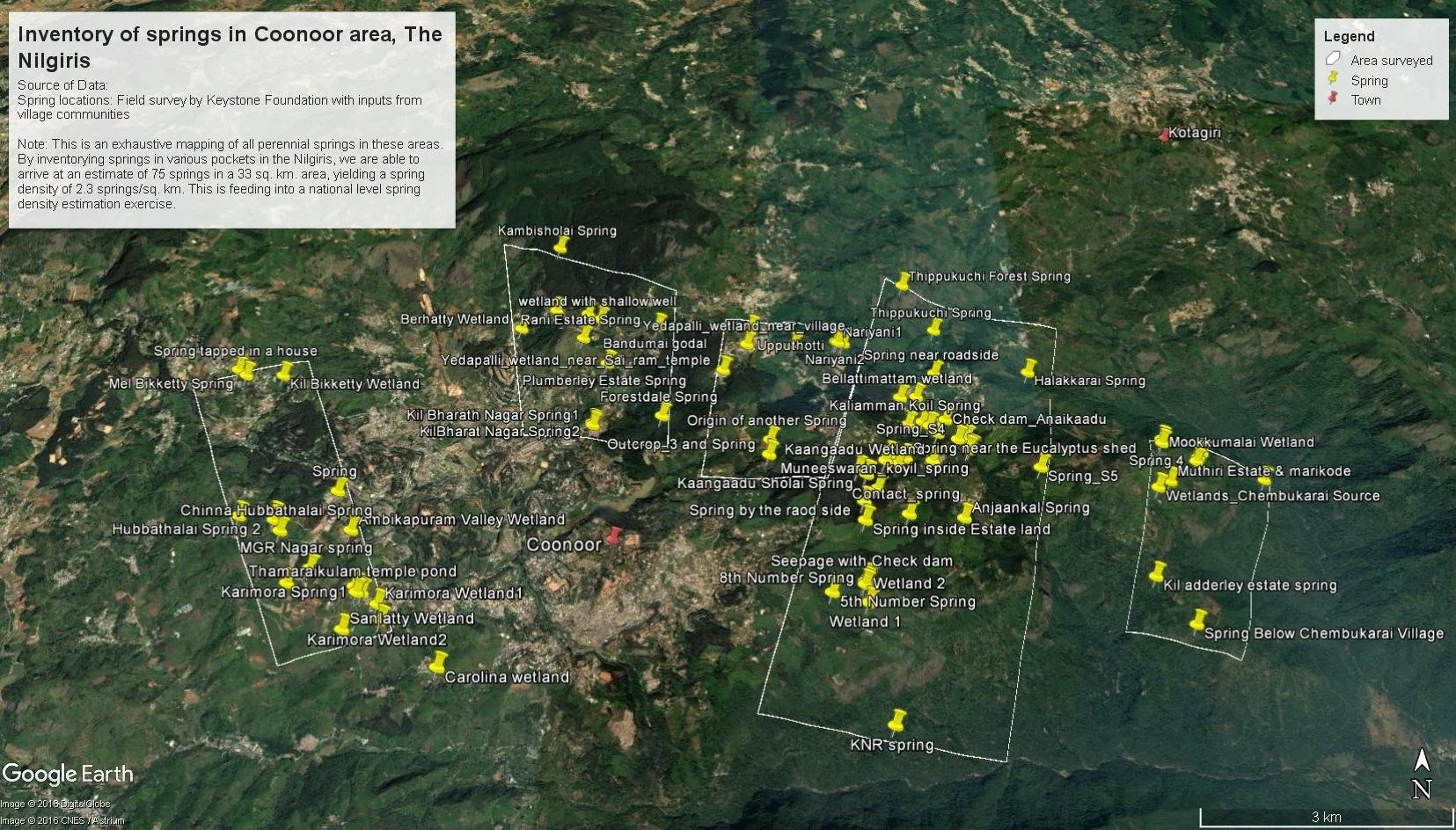

This map shows an inventory of springs in the Coonoor area

This mapping is part of the Springs initiative, a collaboration between NGOs, researchers and government partners working to protect springs across India. In hilly regions like the Nilgiris, these springs are often the only source of clean drinking water for the whole community. By mapping each spring and creating the first atlas for the region, Keystone is building a powerful tool for protection and planning.

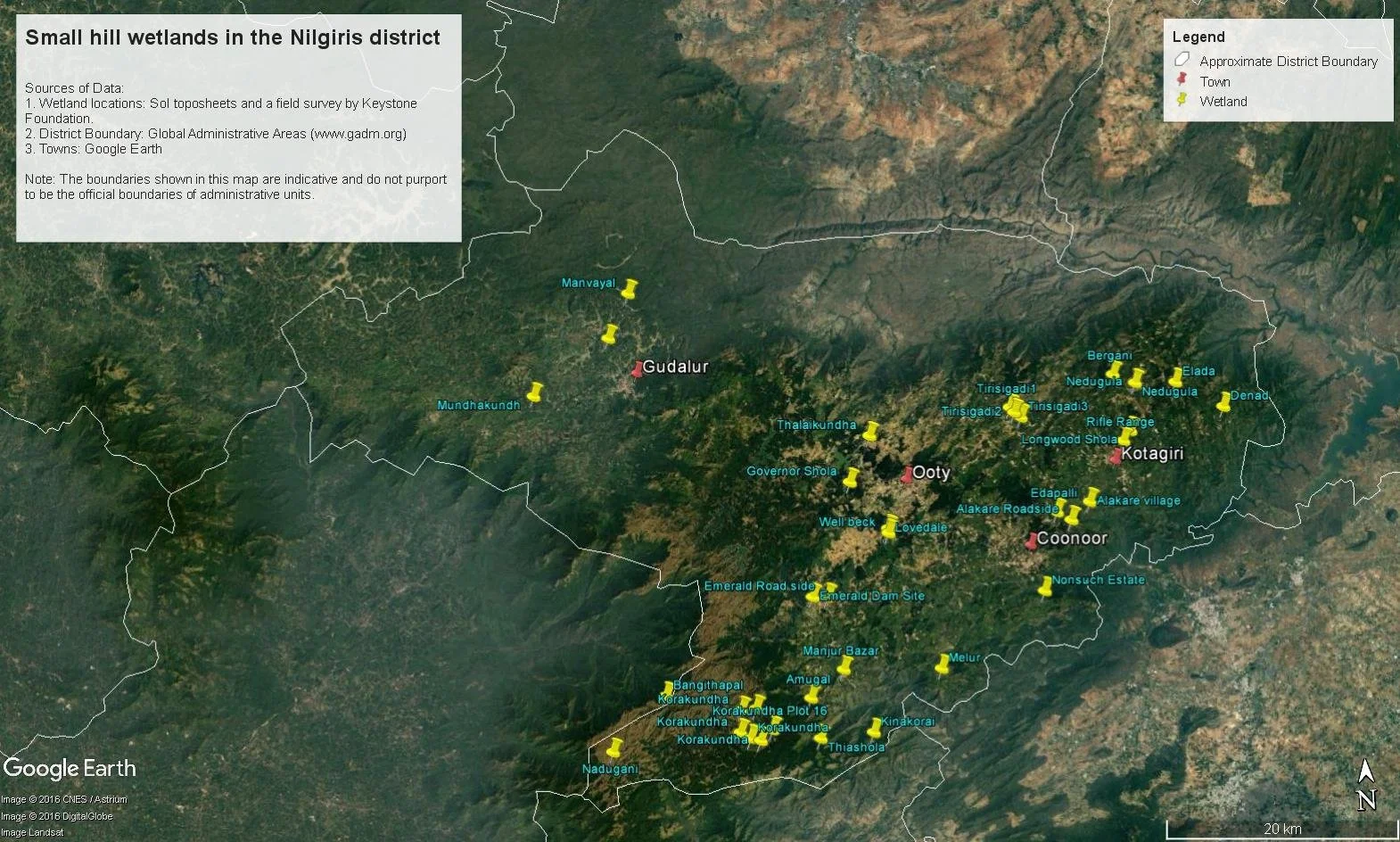

A map of the wetlands in the Nilgiris district

But these maps are more than points and lines. They tell stories of change: of springs that have slowed to a trickle because of nearby groundwater extraction, of wetlands polluted by upstream sewage, of traditional springsheds disrupted by agricultural runoff. With this evidence, communities and governments can take targeted action, whether that’s restoring degraded ecosystems, improving waste management, or protecting land from overdevelopment.

“Changing land use, ecological degradation, exploitation of natural resources and climate change are cutting down on the number of springs and the amount of water that flows through them.”

-T. Balachander, Program Coordination, Keystone Foundation

Keystone’s water mapping efforts now support 4,000 families, protecting springs and wetlands, promoting sustainable livelihoods and helping Indigenous people secure legal title to their traditional lands. In some communities, water testing has revealed faecal contamination, and when layered with mapping data, they’ve identified pollution sources and reduced health risks.

For Balachander, the tools themselves are as important as the outcomes.

“We’ve found that maps, GIS and data are liberating tools. We're trying to make them available to everyone, so that together we can protect access to water, Indigenous communities, the environment and biodiversity. India and the whole world will be better for it.”

-T. Balachander, Program Coordination, Keystone Foundation

Read the full article ‘Keystone Foundation’

Google Maps goes to the Arctic community of Cambridge Bay

In 2012, the Cambridge Bay community invited the Google Maps team to come and help map their community. The goal was simple but powerful; to make their community visible online.

“This is where I live. It’s cold for one and it’s dark most of the year, it’s home. I want people to see what it looks like where I live…It’ll be great to see our community online finally.”

-Christopher Kalluk, GIS and IT Coordinator, Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated

Residents came together for a ‘Map Up’ workshop, learning how to use Google Maps to update the digital map of their home. Streets, landmarks, community spaces, every edit added detail and accuracy, ensuring the online version of Cambridge Bay truly reflected life on the ground.

“This is a very unique cultural lifestyle, I felt it should be shared with the world.”

-Christopher Kalluk, GIS and IT Coordinator, Nunavut Tunngavik In

Watch the full video ‘Google Maps goes to the Arctic community of Cambridge Bay’

These stories from around the world show that cultural mapping can take many forms; from protecting sacred waters, to preserving language and songlines, to making remote communities visible to the world. While the tools and landscapes differ, the heart of this work remains the same: it’s about centering local voices, honouring place and creating maps that carry meaning far beyond the page.

Cultural mapping isn’t just a record, it’s a living, evolving process that connects past, present and future. It empowers communities to tell their own stories, safeguard cultural knowledge and strengthen their connection to Country.

At Winyama, we’ve worked alongside communities to document and protect cultural knowledge through mapping, from recording traditional place names to capturing stories tied to Country. Our recent project with the Karri Karrak Aboriginal Corporation is a powerful example of this work in action, blending local knowledge with modern mapping tools to preserve language, history and connection for future generations.

Read More about the Karri Karrak Cultural Mapping Project

If your organisation or community is looking to capture and protect knowledge, stories and places, Winyama can help. Our cultural mapping services bring together respectful engagement, the latest technology and software to ensure your map reflects your unique connection to Country.